Invasive non-native species (INNS) are species that have been intentionally or unintentionally introduced outside their native range and pose significant ecological and economic threats. These threats exist through competition with native species, disruption of ecosystems and costs associated with biofouling of vessels and marine infrastructure.

In Scotland, there is a policy response to introductions of the invasive colonial tunicate, carpet sea squirt (Didemnum vexillum), from its native range in Japan. This species has now spread globally with confirmed reports from New Zealand, USA, Canada, widespread in northern Europe and even reported in warmer waters of the northern Mediterranean Sea. Once introduced, it reproduces rapidly and can compete for space with native organisms and smother sessile species such as mussels, seaweed or other native tunicates.

Carpet sea squirt can grow into thick carpets on artificial man-made structures including pillars and pontoons at recreational marinas and harbours and have an impact on shellfish aquaculture by overgrowing trestles, ropes and live shellfish stocks (Figure 1). Without intervention, established populations of carpet sea squirt can pose long-term and irreversible threats to marine biodiversity as well as have an economic impact on marine aquaculture and the marine leisure industry. Known pathways of its anthropological spread include shipping, via hull fouling and ballast water transfer, recreational boating and movement of aquaculture equipment and stocks. It can spread further by larval dispersion and fragmentation of suspended colonies.

Figure 1: Carpet sea squirt on aquaculture trestles and wild shellfish.

In Scotland, carpet sea squirt was first confirmed in 2009 at Largs Yacht Haven Marina (Firth of Clyde, Clyde Scottish Marine Region (SMR)) and, following a survey of the local area (2010), it was observed at various other locations including Fairlie Quay Jetty, Fairlie moorings and Clydeport Jetty (Beveridge et al., 2011). More recently, carpet sea squirt has been reported in two active aquaculture sites and a further yacht marina: in Loch Creran (Argyll SMR), north of Oban (in 2016) (Cottier-Cook et al., 2019); in the Fairlie area of Firth of Clyde (in 2017); and in Portavadie Marina (in 2017) (both Clyde SMR).

Marine Scotland response and biosecurity

Marine Scotland is leading a national response to invasive non-native species, including the development of management measures, encouraging vigilance and reporting, and developing biosecurity advice.

Improving biosecurity, i.e. the actions people can take to minimise introduction and spread of INNS, is key to their control and containment. Marine Scotland has contracted consultants who specialize in marine biosecurity and sustainable boating to engage with marine users on an individual basis to understand their activities and help them consider biosecurity measures which could both reduce the introduction and effect of carpet sea squirt and be operationally achievable. In March 2020, the Loch Fyne Community Biosecurity Plan was published to help advise marine users of steps they can take to protect both the environment and their own interests from carpet sea squirt, and help slow its spread.

This community-based approach had previously been adopted in 2017 when the first Community Biosecurity Plan was produced for Loch Creran. An advantage of this approach is to enable marine users to take ownership of biosecurity measures by providing the most up-to-date information to support them. It is tailored to the specific geographic area and the needs of the marine users therein, ensuring it is as relevant as possible.

Monitoring of carpet sea squirt presence in Scotland and surveillance techniques

Surveillance and monitoring of INNS in the marine environment using traditional techniques is very challenging, resource intensive and relies on the expertise of highly skilled taxonomists to accurately identify any suspected specimens. Until 2016, investigation of marine INNS introduction in Scotland was ad-hoc with no targeted annual surveillance. Since the carpet sea squirt (D. vexillum) finding on the shellfish farm in Loch Creran, annual full farm surveys have been completed at this site in order to identify the extent of the infestation and to help inform future containment and control options.

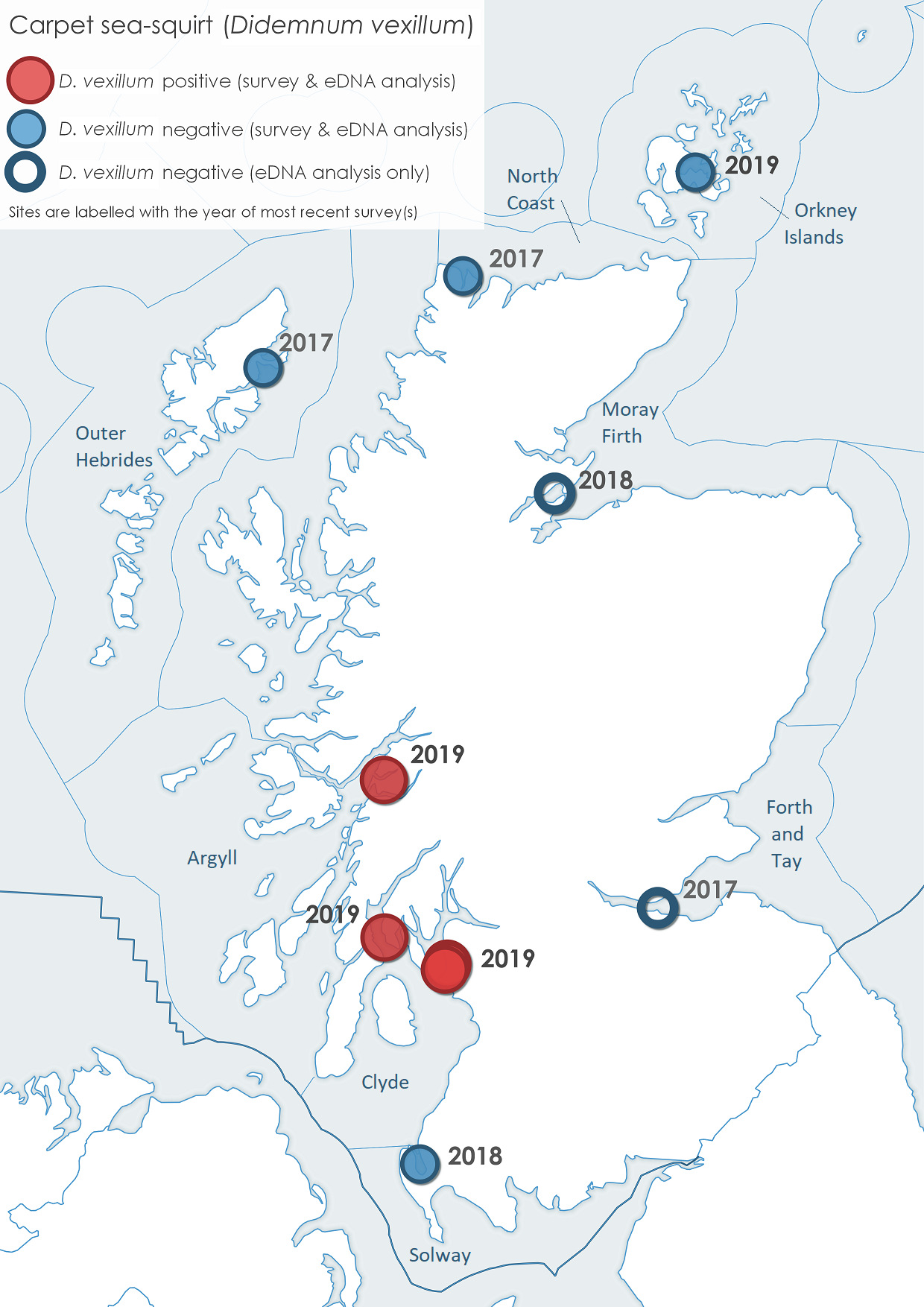

Between 2016-2019, surveillance efforts to improve knowledge of the presence and spread of carpet sea squirt has strengthened with annual surveys being completed at multiple additional sites, including recreational marinas and aquaculture farms (Figure 2).

The traditional monitoring approach to survey for carpet sea squirt (D. vexillum) involves rapid assessments relying on visual assessments of its presence, often aided by a pole-mounted underwater video system. In addition, remotely operated vehicle (ROV) systems have been trialed more recently to survey submerged structures.

Marine Scotland is also exploring novel and cost-effective molecular approaches for INNS surveillance. Detection of DNA shed into the marine environment by living organisms, termed environmental DNA (eDNA), can be used as an indication of presence of carpet sea squirt even before it can be seen visibly growing at a given site, providing an opportunity for faster interventions. In this way, INNS surveillance can be significantly scaled up as seawater samples can be collected at sites by site managers, farm owners or even the general public and posted to Marine Scotland for analysis. Environmental DNA monitoring has been carried out on a small scale across Scotland between 2016-2019 and carpet sea squirt presence data correlated with the data obtained by the traditional survey methods (Figure 2). Moreover, in Largs Yacht Marina carpet sea squirt was detected by eDNA in 2017 and 2018 surveys, despite it not been physically located at this site between the original records in 2009/10 and 2019, when it was visually observed again.

Why is monitoring useful and how is surveillance information used?

Any observed colonies in new locations (or additional colonies in established areas) must be confirmed as being carpet sea squirt. It can appear very similar to other species of native colonial tunicates so correct identification is essential in tracking the spread of this invasive species and determining appropriate action. In addition to visual examination of carpet sea squirt species-specific morphological features, species identification is confirmed using DNA sequencing (Graham et al., 2015).

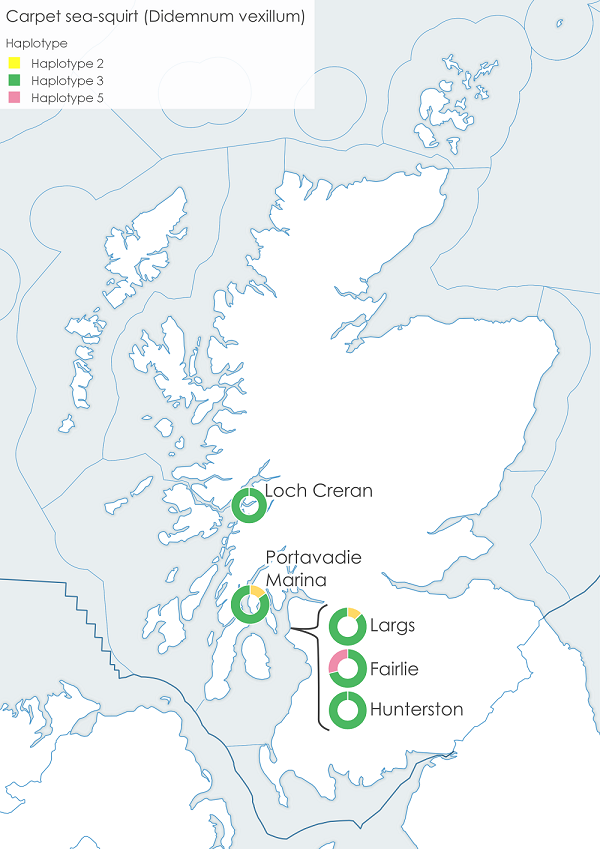

All collected carpet sea squirt colonies are further characterized into genetic haplotypes (a haplotype, genetic variant, is a group of genes, which is inherited together by an organism from a single parent) based on DNA sequence analysis of a mitochondrial gene (Stefaniak et al., 2009). To date up to 24 different carpet sea squirt haplotypes have been identified, with certain haplotypes being only present within its native range while other haplotypes are frequently found in many countries worldwide, including Scotland (Figure 3). Understanding of carpet sea squirt haplotype diversity at different sites can help to further identify and understand pathways for the introduction and spread of the species.

Regular monitoring of sites with established populations helps in understanding the behaviour of the species and to predict future spread. Carpet sea squirt has appeared to behave differently at the various locations throughout Scotland, with growth in some areas appearing much faster than in others.

An adaptive management approach allows for the results of monitoring to directly inform the most appropriate management response, which could include Species Control Agreements/Orders under the provisions of the Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Act 2011. This enables management decisions to be tailored to the specific site, as a single common response is not always appropriate. The appropriate management response can depend on factors such as the local environment, business needs and the extent of spread. Regular monitoring of sites is essential to understand effectiveness of management actions or control measures; it also allows for adaptive management if changes in the established populations are observed.

Further research and future plans

Risk-based, wide-scale surveillance and monitoring of all priority marine INNS (included on the GB Non-Native Species Secretariat Horizon scanning list) will improve protection and help maintain the health and biodiversity of Scotland’s seas and contribute to ensuring that all maritime activities are environmentally and economically sustainable. A Scotland-wide, risk-based hot spot analysis is being carried out to provide detailed lists of potential future monitoring sites. The study builds upon previous work (Tidbury et al., 2016), utilizing data on distribution and intensity of each of the pathways and the associated risk of INNS introduction or spread.

A large scale eDNA project to monitor for carpet sea squirt was also initiated in summer 2019 targeting artificial marine structures such as harbours, ferry terminals, recreational marinas and/or aquaculture related installations and infrastructures. The survey covered 35 sites within the Clyde area including Firth of Clyde, Loch Fyne and Sound of Bute and 14 additional sites (in addition to Loch Creran) in the wider inner sea off the west coast including Loch Linnhe and Loch Etive.

Non-native species (NNS) (sometimes referred to as non-indigenous species) are organisms that are found outwith their natural range as a result of human action. Many coexist with native species with little or no impact, but some can alter the local ecology by smothering and ultimately displacing native species and are referred to as invasive non-native species (INNS). The Non-native species assessment is not based on any established Scotland-wide monitoring programme but rather on incidental reports and some local monitoring programmes. It uses the methods agreed by the Water Framework Directive Technical Advice Group – Alien Species Group. The Case study: Marine non-native species monitoring in the Orkney Islands is an example of a well-established monitoring programme within a single SMR that provides evidence of any spread of NNS within the Region as well as an indication of new arrivals. The Case study: Carpet sea squirt reports on the occurrence and spread of this INNS and the efforts put in place to minimise its impact. It also serves as a good example of the importance to maintain high levels of vigilance and the need for the capacity to be able to respond quickly to such events.