Natural capital, ecosystem services and the Blue Economy

Ecosystem services: Natural benefits of Scotland’s seas

The natural environment, and the processes that sustain it, provide wide-ranging benefits for people

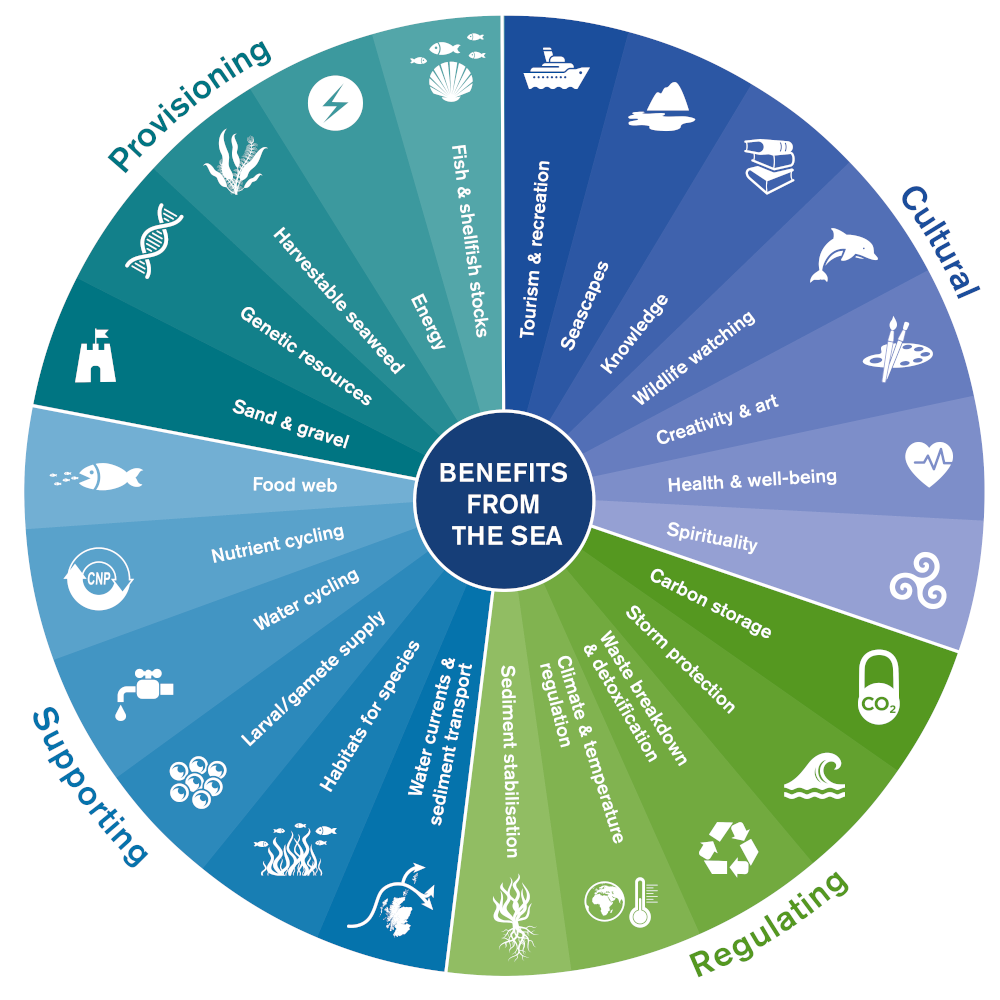

Humans benefit from, indeed rely on, what nature provides. As outlined in the Introduction the overarching concept in respect of benefits to humans from the world’s stocks of natural assets, including geology, soil, air, water and all living things, is that of ‘natural capital’. This encompasses the habitats and ecosystems that provide social, environmental and economic benefits to humans and includes the ocean which is fundamental to life on Earth. The specific functions and resources of nature that provide benefits for people are called ‘ecosystem services’ (Figure 1). Some are direct and tangible, such as fish for human consumption or wildlife that give enjoyment when spotted from a beach, clifftop or boat. Others are less tangible, such as the role of some habitats in limiting coastal erosion (sometimes termed a nature-based solution), or how different species and habitats cycle nutrients, breakdown waste, or help mitigate climate change by sequestering and storing carbon and therefore reducing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. This latter aspect of ecosystem services is placed in the ‘Regulating’ category (elsewhere this is sometimes termed ‘Maintaining' but throughout SMA2020 ‘Regulating’ is used (Figure 1)).

Fish at Peterhead market, where 150.9 thousand tonnes were landed in 2017 by UK vessels, valued at £166.7 million. Landings by UK vessels were considerably higher at Peterhead than any other key port in the United Kingdom. Fish and shellfish stocks are grouped under the ‘Provisioning’ category of ecosystem services and is a very direct and tangible service from the sea (Figure 1).

Many ecosystem services provide substantial economic gains or savings to businesses and governments. Coastal tourism, for instance, is a growing feature of the rural economy in Scotland, with visitors attracted by the range of wildlife and scenery. In 2017, marine tourism, which is placed in the ‘Cultural’ category (Figure 1), generated £594 million Gross Value Added (GVA). This accounts for 0.45% of the overall Scottish economy and 12% of the marine economy GVA (Scottish Government, 2020a).

Figure 1: Examples of the benefits from the sea which are many and varied. They can be grouped into ‘Supporting’, 'Regulating’, ‘Cultural’ and ‘Provisioning’. © NatureScot.

Tourism intensity, assessed on the basis of total nights spent per thousand inhabitants, is higher in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland than the coast of mainland Spain or France.

Weaver et al, 2020

Many benefits cannot easily be defined in monetary terms, but help to sustain the well-being of culture, society and individuals, including physical health and mental well-being (a ‘natural health service’). Protection and enhancement of these ecosystem services are therefore a fundamental component of Scotland’s long-term economic and social prosperity. Given the many human activities that are having an impact on the seas around Scotland, and the rate of change due to the increasing concentration of atmospheric greenhouse gasses, the benefits will likely diminish without appropriate interventions. At the same time, delivering seas that are clean, healthy and biologically diverse will help ensure a high level of productivity. Ensuring that ecological functions are maintained, will undoubtedly benefit humankind. However, finding the optimal balancing point is far from easy since many of the benefits are depending on a number of factors as are the consequences of any specific human activity. An example of where society has responded and adapted to the availability of significant natural resources is Mallaig. This town on Scotland’s west coast was developed to act as the service port for a new railway, opened in 1901, to exploit the large quantities of herring caught in the seas off the west coast. Eventually, the herring fishery declined. However, Mallaig remains an active fishing port, but the largest landings (by weight) in 2018 were shellfish, primarily Nephrops (1,097 tonnes), with demersal fish, primarily haddock and monkfish, accounting for 27.7% of landings by weight (Scottish Government, 2019). No pelagic fish were landed in Mallaig in 2018 (Scottish Government, 2019). At the same time, a significant tourist industry is now associated with the West Highland Line to Mallaig, including the Glenfinnan Viaduct, brought to international prominence by the Harry Potter films.

The Glenfinnan Viaduct, a key piece of engineering that enabled a railway line to be constructed between Fort William and Mallaig. Initially used to transport fish landed in Mallaig, the West Highland Line is now a tourist attraction due to the viaduct featuring in the Harry Potter films. © Lorne Gill, NatureScot.

It is clear that human activities and natural disturbances are having a direct impact upon species and habitats, and can have an indirect impact upon species and habitats via changes to the physical or chemical aspects of the marine environment. These changes can influence the biological, and in some cases, economic productivity of an area. For example, the introduction of organic contaminants or excess nutrients can have a significant impact on the biology as well as the appearance and other sensory stimuli experienced by people when visiting the coast, their senses having an effect on how they perceive the sea. This can diminish their feelings of enjoyment and well-being. These features are described in brief below. More information can be accessed by clicking on the relevant tiles at the bottom of the page.

The physical and chemical marine environment and climate change

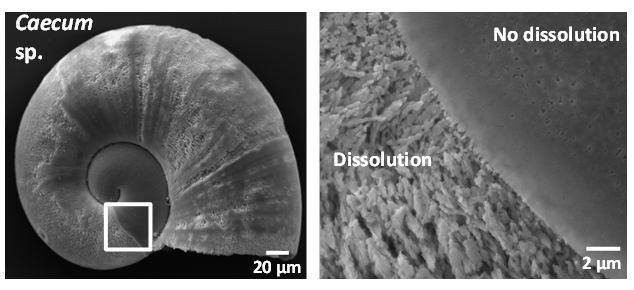

The physical (e.g. temperature range) and chemical (e.g. salinity, dissolved oxygen concentration, dissolved organic carbon, aragonite saturation*) characteristics of the sea underpin the viability, distribution and functioning of species and habitats, and therefore the ecosystem services to which they contribute. The ocean also plays a fundamental role in the cycling of carbon. Climate change and ocean acidification, together with the exploitation of many of the natural resources, currently exert a detrimental influence on these characteristics. This will increase in future and have an impact on the benefits provided by the seas around Scotland unless measures are taken to reverse the changes that are currently being observed. As an example, shell dissolution has been observed in planktonic gastropod larvae collected from the Marine Scotland sampling site off Stonehaven, north-east Scotland (Figure 2). This was due to a decrease in the aragonite saturation. The future impact of this on food webs remains unknown. However, disruption to the carbon cycle in coastal ecosystems is of concern because of the disproportionately high rates of primary production in coastal ecosystems compared with offshore regions.

Figure 2: Evidence of shell dissolution in a planktonic gastropod larvae specimen associated with a decrease in aragonite saturation.

*Aragonite is the more soluble of the two crystalline forms of calcium carbonate. Aragonite saturation is basically an indicator of the availability of calcium carbonate to animals that build shells and form coralline structures.

Productive seas

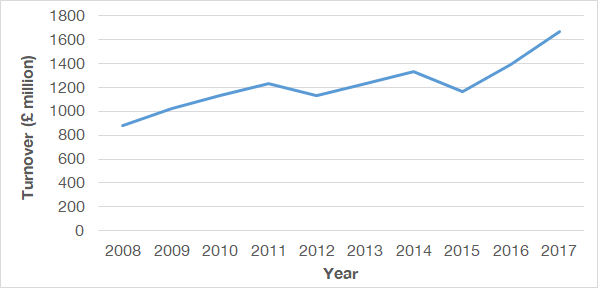

People benefit financially from seas that are healthy. Populations of fish and shellfish, supported by suitable habitats, where there is effectively regulated fishing mortality, have the potential to provide viable fisheries for the long-term. Clean, safe and healthy seas support the production of farmed fish (Figure 3) and shellfish, provide conditions in which wildlife can thrive, and furnish opportunities for tourism, coastal recreation and related businesses. There is an inextricable connection between the state of the sea and the productivity of the sea which, unless properly understood, runs the risk of poor planning decisions being made that have an impact on the health of the sea. In addition, the marine economy provides many jobs, be it at ports and harbours or through ship building and marine transportation. Furthermore, oil and gas has been extracted from the seas around Scotland and, more recently, marine renewable energy has developed significantly. With improved understanding of the impacts of human activities on the seas, these can be managed to safeguard their long-term viability.

Figure 3: Annual turnover for commercial fishing and aquaculture in Scotland, 2008 – 2017 (2017 prices). Source: Scottish Government, 2020.

Clean and safe seas

Anthropogenic sources of contamination (synthetic organic chemicals, heavy metals, plastics), nutrient imbalance, or noise, can have an impact on the physical health, behaviour and functioning of marine species and habitats. Monitoring of both the concentrations of contaminants and their biological effects continues in the seas. See Clean and safe theme. Significant improvements have been observed over time following developments in on-land processes. However, many species, habitats and physical processes also have important roles in processing, detoxifying and protecting the ecosystem which in turn protects people from the negative impacts. Reductions in emissions, discharges and accidental losses of all types of contaminants, together with an improved understanding in the consequences of impulsive and continuous noise, should deliver cleaner and safer seas in which marine life can thrive, increasing the potential for ecotourism. Generally, the concentrations of contaminants in the seas around Scotland are below those where biological effects will be observed. However, there remain some problem areas.

Recovery of a sample of seabed sediment from a Day grab for chemical analysis on MRV Scotia.

Healthy and biologically diverse seas

Marine biodiversity benefits from seas that are clean, healthy, safe and able to function naturally. In turn, species and habitats (and the processes that support them) play an essential role in maintaining ecosystem health, helping to mitigate potentially damaging impacts, and providing people with many financial, cultural and health benefits. Nature-based solutions, that provide sustainable mechanisms to ensure healthy and biologically diverse seas, are integral to future planning and climate-change adaptation. Furthermore, flood protection by coastal ecosystem creation and restoration can provide a more sustainable, cost-effective and ecologically sound alternative to conventional coastal engineering. In Scotland, coastal protection against rising sea levels includes managing and conserving coastal wetlands. Healthy seas also play a vital role in trapping and absorbing carbon dioxide. The seagrass meadows, kelp forests, maerl beds, reefs and intertidal saltmarshes all contribute to trapping carbon while the surficial sediments (top 10 cm) of the mapped area covered by SMA2020 contains an estimated 1,515 ± 252 Megatonnes carbon (Smeaton, Austin & Turrell, 2020).

Saltmarsh occurs in scattered pockets around Scotlands coasts especially in relatively sheltered areas such as at the head of sea lochs and in the major estuaries and Firths such as the Solway and at Aberlady Bay in the Forth. © John M Baxter.

Scotland’s Marine Protected Area (MPA) Network

MPAs were largely set-up to conserve specific species, habitats, geology and landforms and the network as a whole now covers 37% of Scotland’s seas by area, which includes the designations made in 2020. It was 22% in 2018 at the end of the assessment period. Management measures within specific MPAs protect the features for which the sites were designated in particular and have the potential to make a contribution to protecting marine natural capital and associated ecosystem services. Although MPAs in Scotland are principally designed as conservation tools using a feature-based approach for site selection, ecosystem services can be supported, or potentially enhanced, by their designation. This can be illustrated using the South Arran Nature Conservation MPA which covers an area of 250 km2. The site was designated for its diversity of animals and plants, including maerl beds, kelp and seaweed communities, and burrowed mud. It also contains a significantly sized seagrass bed. The socio-economic impact of MPAs, with a focus on Scottish fisheries, is covered in a Case study.

Maerl, a type of 'coralline’ algae, deposits lime (calcium carbonate) in its cell walls as it grows, creating a hard, brittle skeleton. It forms purple-pink hard seaweed that forms spiky underwater ‘carpets’ on the seabed, known as 'maerl beds’ (see Case study). Maerl beds are an important habitat for many small marine plants and animals which is part of the reason why maerl beds are a Priority Marine Feature and are also included within MPAs. Maerl beds are also a store of blue carbon. ©Lisa Kamphausen, NatureScot.

Coasts and seas for human health

A trip to the sea has long been recognised as being ‘good for you’. In more recent years, researchers have begun to understand why this is the case, confirming that Scotland’s seas are important for human physical and mental health. It has now been shown that living close to the coast makes it more likely that humans will achieve the recommended levels of physical activity. Physical activities also benefit our mental health, with research showing that the greatest feelings of happiness are found during time spent in marine and coastal areas (Gascon et al., 2017).

Social attitudes to the sea

There needs to be greater consideration given to how people interact with the marine environment and what they value about it, both of which have implications for policy development and management of human activities that have an impact on marine ecosystems.

A recent investigation by Scottish Government, published in March 2020, focused on the attitudes of Scottish residents with respect to:

- uses of marine and coastal areas

- environmental concerns

- marine economic activities

- the management of Scotland's marine environment

A key finding was that Scottish residents have a huge appetite for learning about the marine environment with many having a strong desire to know more. Humans are part of the ecosystem, and Scottish residents, when discussing in groups, showed strong support for maximizing the benefits derived from the marine environment to them whilst protecting resources for future generations.

The ongoing supply of the wide range of benefits to people and nature will only be assured if the natural process can continue.

This Topic is applicable mainly to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 13 (Climate action) and 14 (Life below water) and also contributes to many other SDGs.

Themes

Literature

|

, 2017. Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: A systematic review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 220, pp.1207–1221. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ijheh.2017.08.004. |

|

, 2019. Scottish Sea Fisheries Statistics 2018, The Scottish Government. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-sea-fisheries-statistics-2018/. |

|

, 2020. Marine economic statistics 2017: corrected April 2020, Edinburgh: The Scottish Government. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-marine-economic-statistics-2017/ . |

|

, 2020. Re-evaluating Scotland’s sedimentary carbon stocks. Scottish Marine and Freshwater Science, 11(2), p.16. Available at: https://data.marine.gov.scot/dataset/re-evaluating-scotland%E2%80%99s-sedimentary-carbon-stocks. |