In the last ten years there has been a significant increase in research relating to basking sharks off the west coast of Scotland. New statistical modelling work and the use of cutting-edge technologies, for example telemetry, Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV) and camera tags, have significantly improved the understanding of the distribution, migration, habitat-use and underwater behaviour of basking sharks.

Background

Basking sharks, the world’s second largest fish, toothless giant, which feeds solely on plankton, are included on Scotland’s list of Priority Marine Features (also see Priority Marine Features case study). These giant sharks, up to 10 m in length (Figure 1), have been recorded all around Scotland but are found in larger numbers in the Sea of the Hebrides on the west coast, mainly during the summer months. Basking sharks were the subject of a targeted fishery until 1992; it is unclear how well numbers have increased since then, although there are some positive signs including a trend of increased observations of larger sharks in a public sightings database (Bloomfield & Solandt, 2011) and boat-based surveys (Witt et al., 2012) and the observation of close to 1,000 individuals during a single day boat survey (Booth et al., 2013). There are tentative estimates of basking shark numbers from small areas on the west coast (Booth et al., 2013; Gore et al., 2016), but there are no agreed population assessments for basking sharks in Scotland, the North-East Atlantic or globally, with little information on trends. Basking sharks are now a protected species in Scotland, are on the OSPAR list of Threatened and Declining species and classed as globally Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Their low fecundity, lengthy maturation time, surface behaviour and importance of key areas (seasonally and year on year) make them vulnerable to a variety of pressures and limit their ability to recover from impacts.

New discoveries and analysis

A variety of different survey and research work focused on basking sharks has been undertaken off the west coast since publication of Scotland’s Marine Atlas (Baxter et al., 2011). New statistical modelling work and the use of cutting-edge technologies have all helped to increase understanding. Some examples are given below.

Site fidelity and seasonal migration

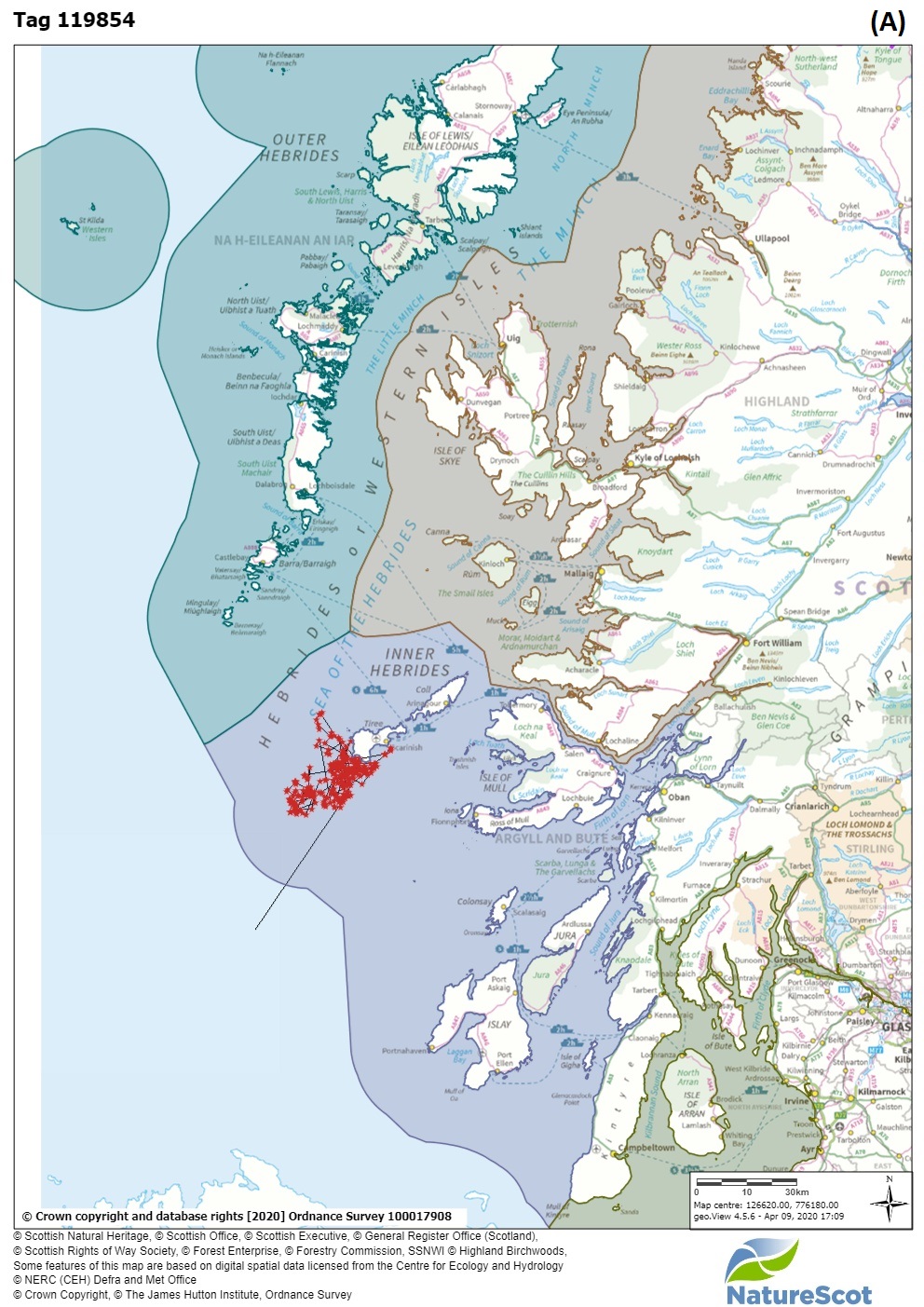

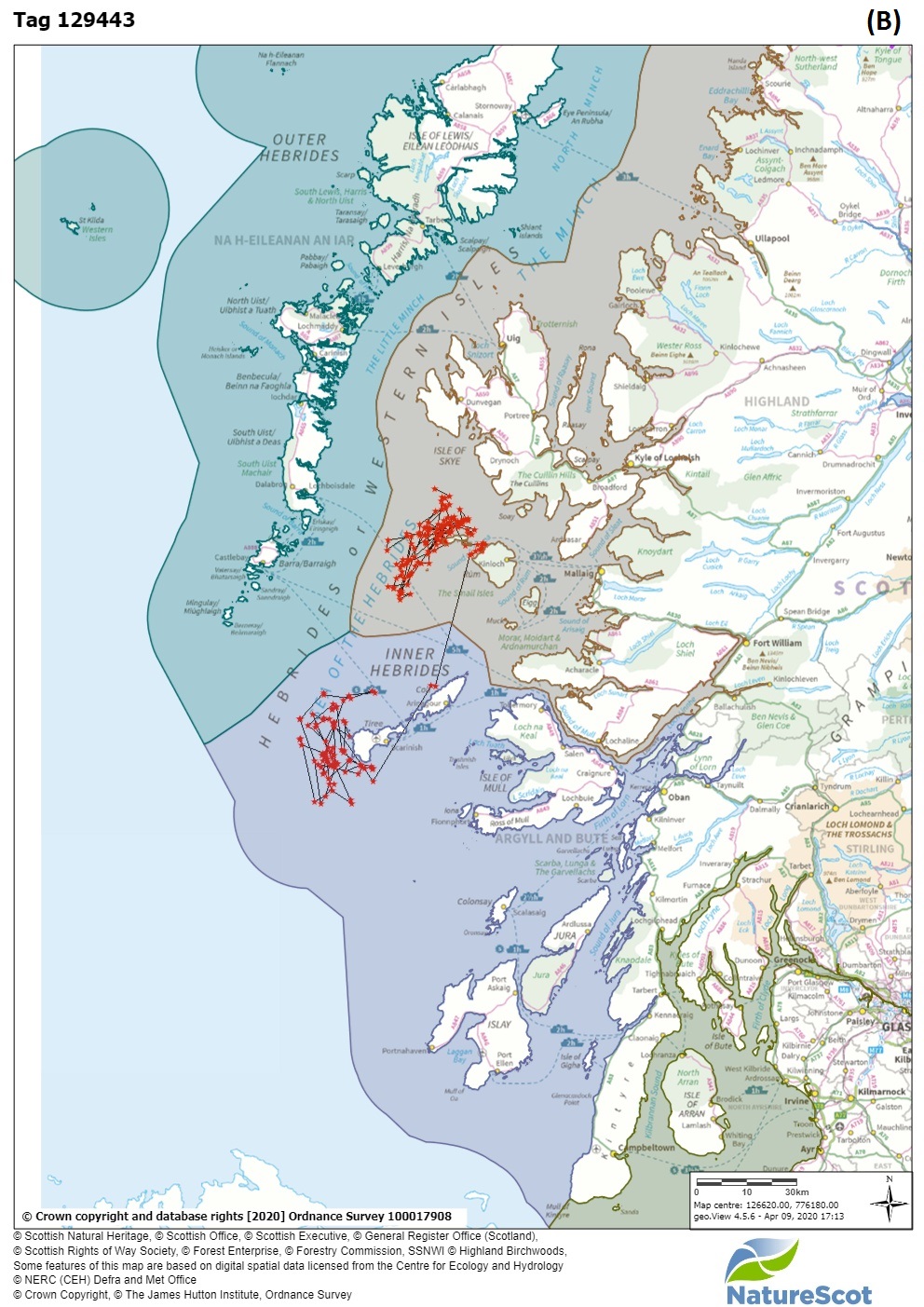

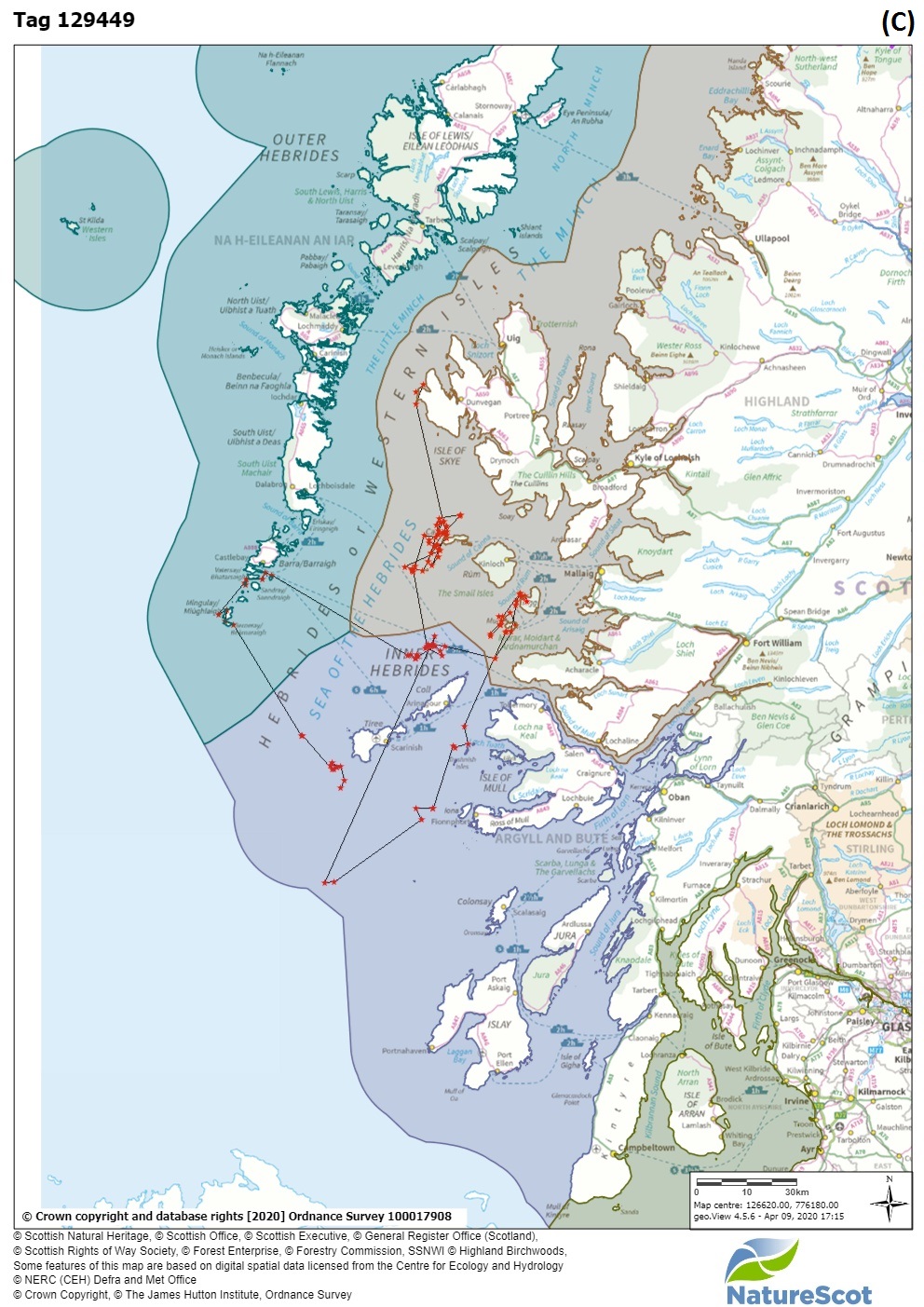

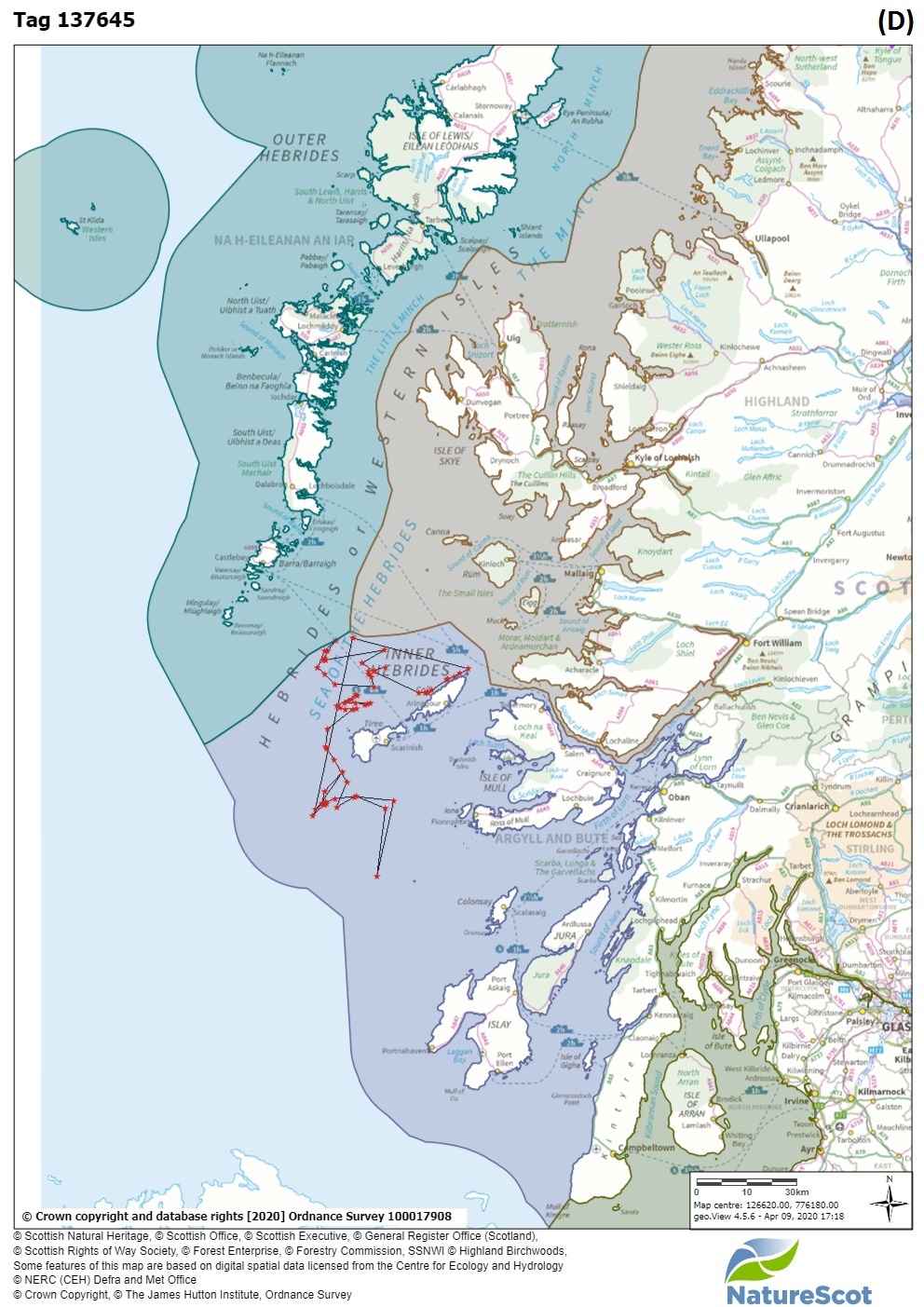

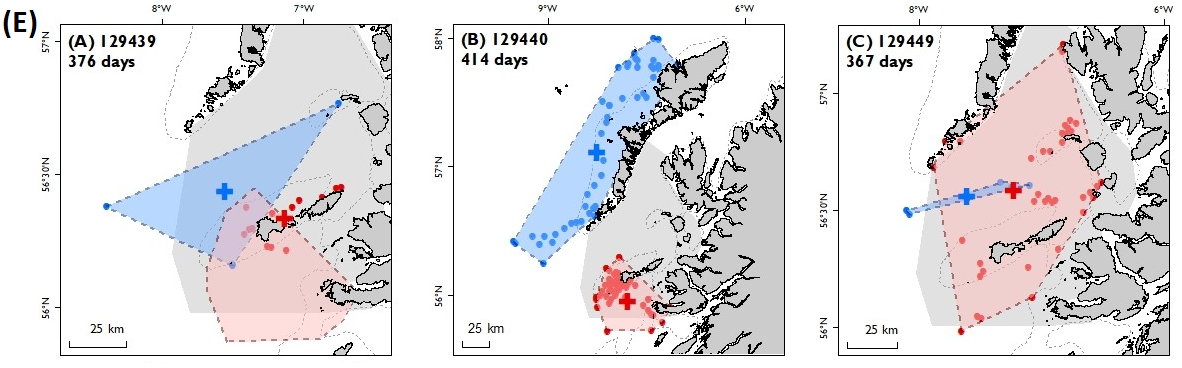

A partnership between the University of Exeter and NatureScot was formed in 2012, and using a variety of satellite telemetry technologies (Figure 2) provided the first clear evidence of basking shark site fidelity within the Sea of the Hebrides during summer months (Doherty et al., 2017a, Figure 3 A-D). This work was undertaken around the islands of Tiree and Coll, including the reefs around Skerryvore to the southwest of Tiree, where large numbers of sharks were known to aggregate. The first evidence of individual sharks returning to Scottish coastal waters in consecutive years was also obtained, indicating basking sharks show inter-annual site fidelity (Doherty et al., 2017a, Figure 3 E). This research built on the work of Speedie et al. (2009) and used the tagging deployment methods and information shared by researchers in the Isle of Man. Sharks tagged around the Isle of Man have been shown to travel north to the west coast of Scotland during summer months (Dolton et al., 2020).

Figure 2: A. Satellite tags – from top to bottom; SPOT, mini PAT. B. SPLASH tags (Wildlife Computers). C. Basking shark showing towed SPLASH tag floating behind tip of dorsal fin, tethered by a plastic monofilament attached to a dart fixed into muscle at base of dorsal fin.

Figure 3: Site fidelity – maps A to D show individual basking shark surface locations from satellite tags deployed during 2012, 2013 or 2014. They show a variety of surfacing behaviours from July until the end of September, although these are primarily clustered within the Sea of the Hebrides indicating site fidelity (see Doherty et al., 2017a for further details). Coloured shaded areas show Scottish Marine Regions. E. Maps showing the surface locations of 3 sharks during summer months in 2013 (red dots) and their positions after their return to Scottish waters in summer of 2014 (blue dots) after having travelled south in winter. Crosses show mean centroid points of all locations with shaded areas showing smallest area between all locations (Minimum Convex Polygon) from Doherty et al. (2017a).

Seasonal migration by basking sharks in the UK was first demonstrated by Sims (2003) using early pop-up satellite archival transmitters. This revealed individual sharks following UK shelf-break fronts where productivity is high. Following recent work in Scotland (Doherty et al., 2017b), different individual post summer migration strategies have been suggested from the analysis of 70 satellite tagged basking sharks (see Figure 4):

- some sharks spend the colder months in areas off the Scottish continental slope;

- others migrate further south to the Bay of Biscay using either the Celtic Sea or to the west of Ireland; and

- others travel to the Azores before returning to Scotland the next summer.

Further to this work, Dolton et al. (2020) showed one tagged shark travelled to Moroccan waters for two consecutive winters. Additionally, northerly migration behaviour has been recorded from a basking shark tagged in Scotland (Doherty et al., 2017b) and another tagged in Isle of Man (Dolton et al., 2020), with individuals travelling as far as the waters of the Faroe Islands and Norway respectively.

Figure 4: Seasonal migration – the schematic map shows three different types of post summer migration behaviour (based on 70 satellite tagged sharks and as suggested by Doherty et al. (2017a)). Dashed dotted line represents northerly migration (from Dolton et al. 2020).

Autonomous underwater vehicles and towed camera tags

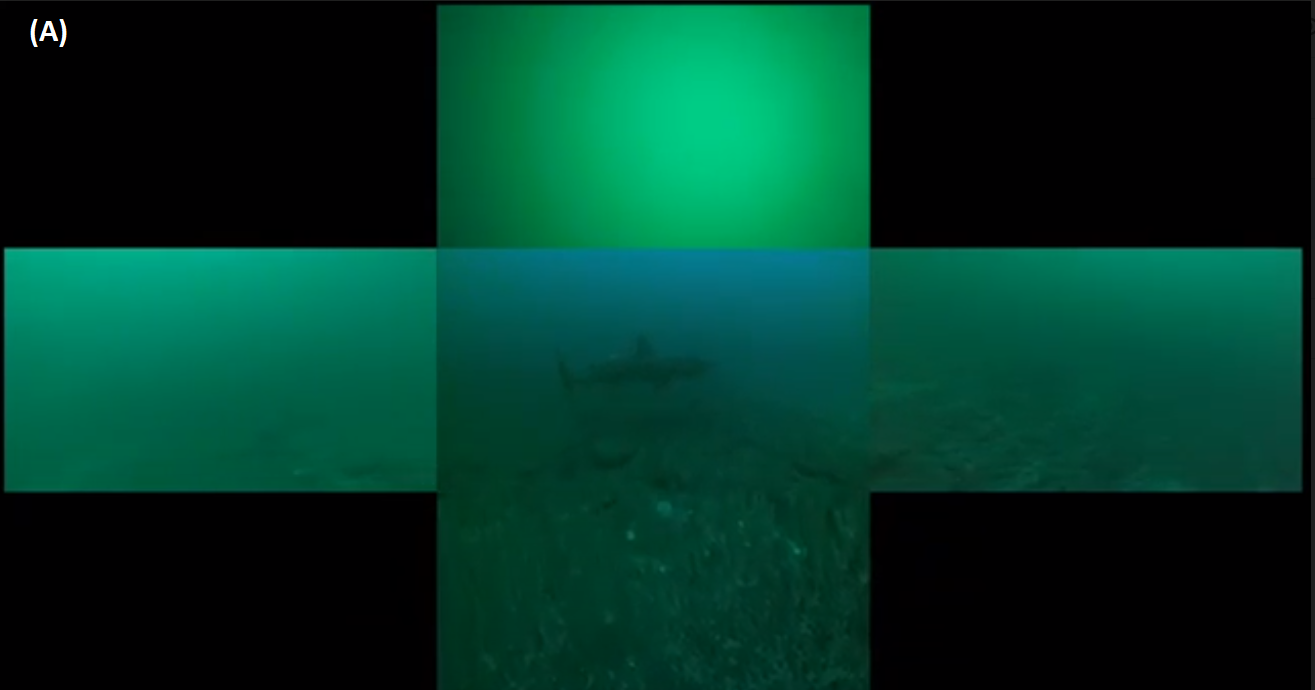

In 2019, international collaborative work involving project partners NatureScot, University of Exeter, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Sky Ocean Rescue/World Wide Fund for Nature investigated the underwater behaviour of basking sharks using an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) equipped with video cameras, that was designed, built and operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (see Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution – AUV technology explained) (Figure 5 C). The first successful tracking of basking sharks using the AUV revealed sharks spent considerable time swimming near the sea bed around the islands of Coll and Tiree (Figure 5 A & B). The analysis of these data continues but is giving detailed information on the sub-surface tracks of sharks and insights into the types of habitats and associated environmental parameters the sharks utilise off the west coast of Scotland (Hawkes et al., 2020).

Figure 5: A. Merged images from 5 video cameras aboard the AUV (centre image is forward, left, right, up and down). B. Forward view from AUV of shark swimming close to seabed with mouth closed. C. The AUV on board vessel before being deployed. All photos © Amy Kukulya, Oceanographic Systems Lab, WHOI.

Research using towed camera tags by The University of Exeter and NatureScot partnership has revealed new basking shark group behaviour in Scotland; footage showed a number of sharks close to the sea bed, moving very slowly or stationary and almost touching each other (Figure 6, Rudd et al., In prep).

Figure 6: Screen grab from towed video tag footage: three basking sharks are shown - the centre shark is towing the camera (from a tether attached to the thick muscle below the dorsal fin), a second shark is to the left and their pectoral fins are touching, a third shark is directly ahead with its head pointing left (pectoral fin and tail just visible). All sharks are nearly stationary with mouths closed (not feeding).

Statistical modelling

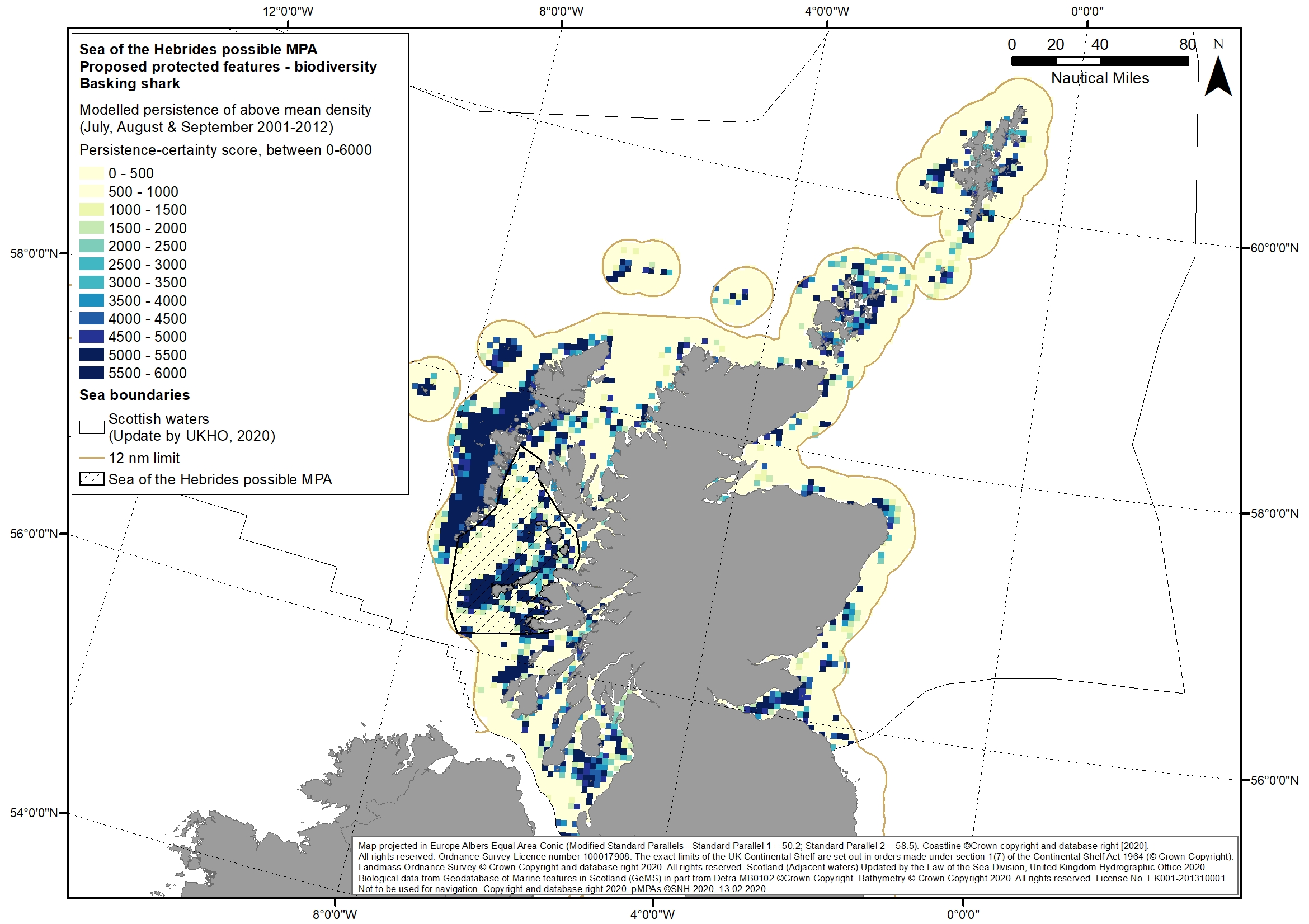

Statistical modelling of basking sharks in Scottish territorial waters has been undertaken to identify areas of importance for the species. This work was part of a wider effort utilising 25 distinct data sets and up to 180,300 km of survey effort (from vessel and aerial surveys) and included 1,116 basking shark observations (see Paxton et al., 2014).

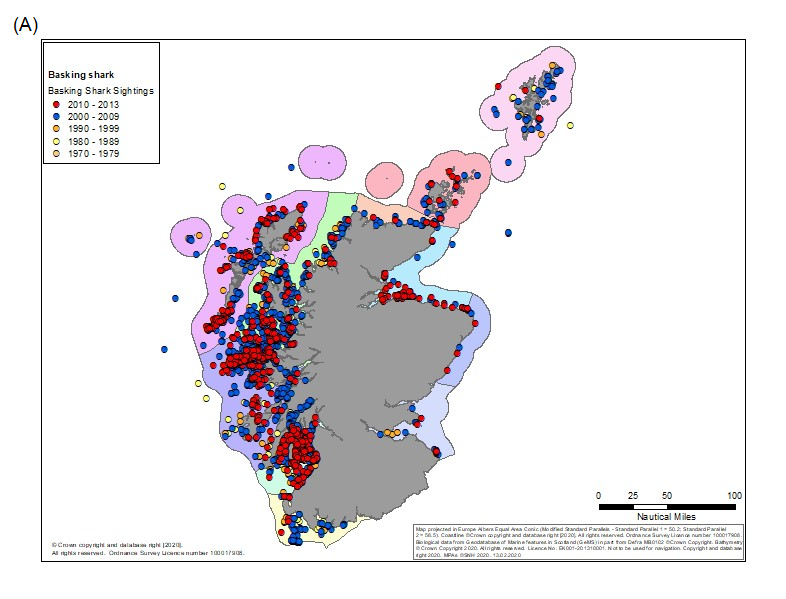

The method relied on combining all available survey data to derive observed (effort-corrected) densities (Figure 7 A). Various environmental data were incorporated into the analysis to enable seasonal and annual predictions about the density of animals in different locations around Scotland to be made.

The work identified areas of persistent use by basking sharks in Scottish territorial waters (Figure 7 B). The modelled areas of importance generally aligned with basking shark effort-corrected sightings data although a large area to the west of the Outer Hebrides, which was data-poor for effort-corrected sightings, was also identified (Paxton et al., 2014).

(A)

(B)

Figure 7: A. Basking shark effort-corrected sightings data. B. Modelled areas of persistent use by basking sharks in Scottish territorial waters. Both based on work of Paxten et al. (2014).

Breaching behaviour

Basking sharks have been observed breaching frequently; a behaviour that involves the animal propelling itself out of the water (Figure 8) and which seems to occur specifically in areas where there are aggregations (Speedie et al., 2009) and areas with higher densities (Hayes et al., 2018). Breaching behaviour in sharks has been suggested as being linked to courtship and breeding, alongside other theories such as parasite removal, signalling and predator avoidance (Gore et al., 2018). There is also now evidence from Scotland to show that individual basking sharks can breach up to four times in quick succession, in areas where sharks seasonally aggregate (Rudd et al., In review). With speeds comparable to predatory white sharks (Johnson et al., 2018), each breach is estimated to be 32 times more energetically costly than routine swimming, suggesting this behaviour needs to have a clear benefit (Rudd et al., In review).

Figure 8: Breaching basking shark. © Colin Speedie.

Genetics

A new technique for obtaining genetic samples from basking sharks was developed in 2013, which allowed sampling from live individuals; this involved wiping a cotton dish cloth along the side or back of a swimming shark to collect skin mucus (Lieber et al., 2013). Analysis of newly developed species-specific microsatellites (Lieber et al., 2015) from the mucus showed there were greater genetic similarities between samples from Scotland, Ireland and Isle of Man than to samples from elsewhere (England, Mediterranean, New Zealand, South Africa, North West Atlantic) (Lieber et al., 2020). Individuals sampled within the North-East Atlantic were found to be more related than expected by chance. Individual sharks can be genetically identified from mucus samples which has revealed one individual returned to Gunna Sound on the west coast in consecutive years, whilst another was sampled on the west coast in one year and then in the Moray Firth on the east coast the following year.

Other work

Citizen science work

A number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have been instrumental in setting-up and or enabling basking shark focused citizen science. For example, the Marine Conservation Society initiated the Basking Shark Watch project in 1987, and sightings records have since been collated within the largest basking shark sightings online database (Figure 9 A; Bloomfield & Solandt, 2008). Another example is the collaborative project between Wave Action and The Wildlife Trusts which used volunteers on board a sailing vessel to help collect effort-corrected sightings data on basking sharks in Scotland (Figure 9 B; Speedie et al., 2009).

Figure 9: Examples of citizen science. A. Marine Conservation Society public sightings data for basking sharks, Scottish Marine Regions are indicated with coloured polygons. B. Volunteers on board sailing vessel collecting basking shark sightings data - a project involving Wave Action and The Wildlife Trusts (Speedie et al., 2009).

SIORC (Sharks, skates and rays in the Offshore Region and Coastal zone of Scotland) - A MASTS Community Project

The SIORC (gaelic for shark) Community Project was launched in 2014, bringing together the science community with elasmobranch knowledge and expertise from across Scotland and further afield. The group is currently involved in producing an overview of elasmobranchs, including basking sharks, in Scotland to aid conservation, which will be published by NatureScot in 2020.

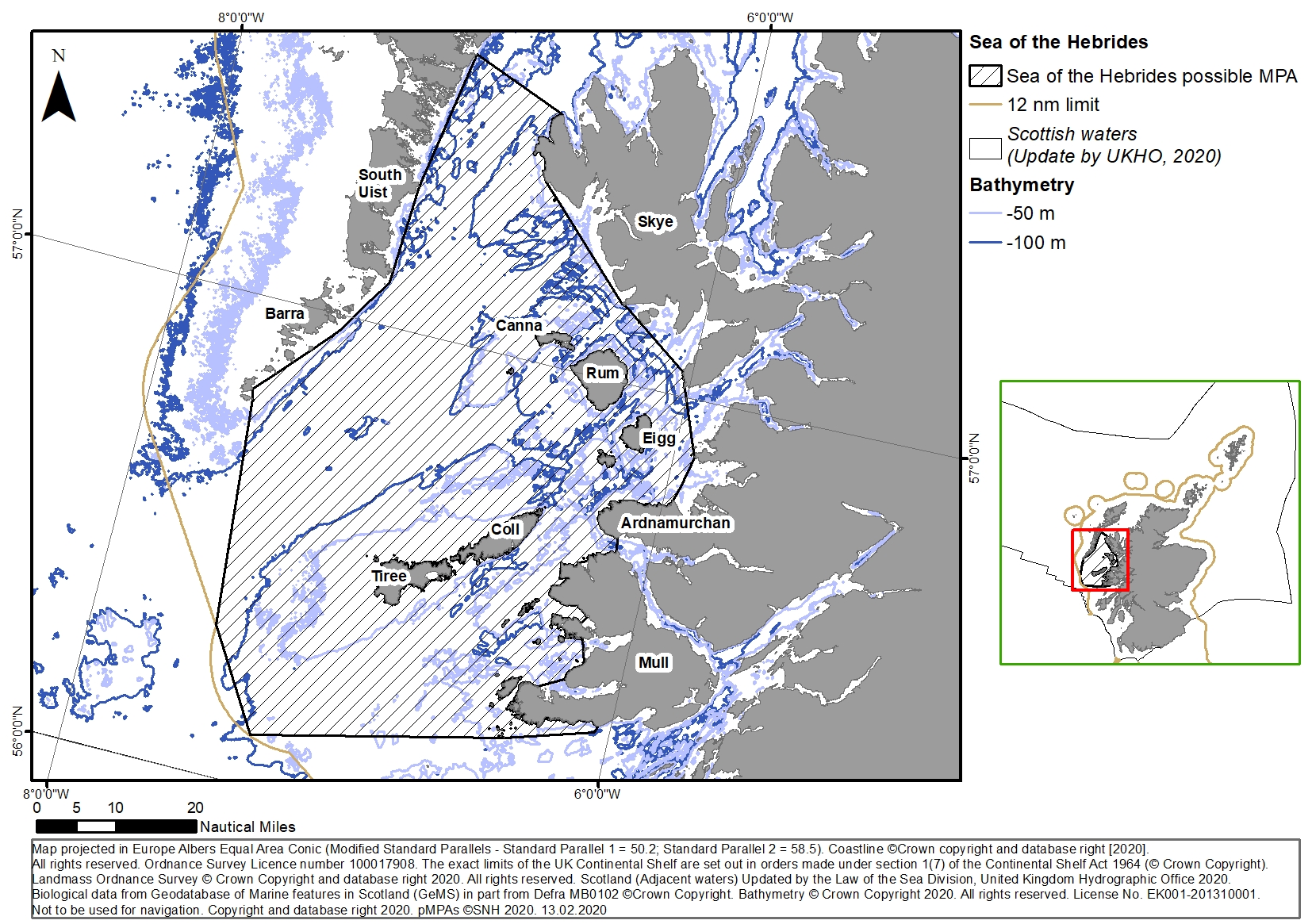

First Marine Protected Area (MPA) for sharks in Scotland

The Sea of the Hebrides MPA, designated in December 2020, is the first area giving protection to a species of shark in Scottish waters (Figure 10) and the largest for a shark species in the North-East Atlantic. The scientific evidence on basking sharks presented above helped in the selection and designation process under the powers and duties within the Marine (Scotland) Act (2010). Basking sharks rely on the productive waters within the Sea of the Hebrides to feed, where they can be seen in large numbers year on year, often displaying courtship-like behaviours; it is therefore possible they use this area to breed. The MPA will provide recognition of the value of Scottish waters, raising awareness of Scotland’s iconic wildlife and encouraging us all to enjoy nature. Appropriate management of marine activities will also help to ensure the basking shark can continue to utilise the resources and habitats within the MPA.

Marine Protected Area

The scientific evidence on basking sharks presented above helped NatureScot provide advice on the potential designation of Sea of the Hebrides as an MPA under the powers and duties within the Marine (Scotland) Act (2010). The evidence shows the Sea of the Hebrides is an area of productive waters that basking sharks rely on to feed, and where they can be seen in large numbers year on year, often displaying courtship-like behaviours; with the possibility of it being a breeding site. The Sea of the Hebrides is likely to continue to be an area where research will focus to further understanding of basking shark and their conservation.

Summary and knowledge gaps

Recent work has led to new discoveries on basking sharks. There is now evidence available that basking sharks show seasonal residency during the summer, and that they return in consecutive years to the same areas on the west coast. Southerly migration occurs during winter months and three different strategies have been observed, including one which shows some sharks remain in deeper waters off the Scottish continental shelf. Areas off the west coast are used persistently by basking sharks in higher densities compared to other parts of Scotland. Many basking sharks show courtship-like behaviour at the surface and underwater, and individual sharks are capable of repeated breaching behaviour in quick succession. Underwater visual evidence has shown individuals spend more time close to the sea bed than previously thought, and new group behaviour has been observed. However, gaps still remain in the knowledge about basking sharks; with questions over their reproductive cycle (breeding and pupping), group behaviour and the extent to which interactions with human pressures are detrimental to them individually and for the species generally (e.g. disturbance, entanglement, collision, and fisheries incidental catch). In addition, collective work is underway to improve the understanding of the data and methods available that will help with future reporting on the status and trends of mobile species across the Scottish MPA network and includes basking sharks.

The seas around Scotland support a wide variety of fish species, some of which have been a source of livelihood, food and culture for centuries. Different components of the fish community have been assessed using different parameters. The Wider fish community assessment is based on 167 different species sampled by the International Bottom Trawl Survey designed to assess changes in demersal (bottom dwelling) fish communities. This includes a range of both commercial and non-commercial species. The Commercial fish assessment is based on the status of the eight species of greatest commercial value to Scotland (mackerel, herring, haddock, monkfish, cod, hake, whiting, saithe) using fishery and survey data. The Inshore fish (estuaries and reduced salinity sea lochs) is undertaken to determine the quality of transitional waters and the assessment is based on six representative inshore sites on the east and west coasts of Scotland. The Deep sea fish assessment is based on data from various scientific trawl surveys that provide a measure of species richness. Scotland has long been renowned for its Salmon and sea trout – two species that spend part of their life cycle at sea before returning to their natal river to spawn. The assessment of these stocks is based on returning fish (catches and count data) for 173 assessment areas which are primarily single river catchments. Altogether these various assessments provide an overview of the status of the different fish stocks, but much remains to be done to fully understand their behaviour and dynamics. The Case study: Basking sharks in Scottish waters for example describes how the use of cutting-edge technologies has greatly increased our understanding of the distribution, migration and behaviour of the basking shark (the second largest fish in the ocean) that frequent the waters off the west coast of Scotland. Similarly, the Case Study: Flapper skate – Loch Sunart to the Sound of Jura MPA describes how a capture-tag-recapture project involving recreational sea anglers, data storage tags and acoustic arrays have greatly improved our understanding of the ecology of the skate and consequently informed the necessary management measures needed to ensure their protection. The Case study: Sandeels in Scottish waters describes this fish stock that is an important component of the food web.