The European native oyster (Ostrea edulis) (Figure 1) was once widespread in European waters. It ranged from the Norwegian coast, around the British Isles and western continental coasts to the northern coast of Morocco, parts of the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea. The species was once a common part of Scotland’s natural heritage, with billions of oysters forming dense beds over wide areas of the seabed, including estuaries and sea lochs. Globally, oysters of all species have declined significantly over the past 150 years. Factors contributing to the decline are over-exploitation, pollution, habitat deterioration, diseases, Allee effects (i.e. a decline in individual fitness at low population size or density, that can result in critical population thresholds below which populations crash to extinction), and introduced pests and parasites.

Figure 1: The European native oyster, Ostrea edulis. © NatureScot.

There is evidence of humans harvesting oysters dating back to Neolithic times to be found in shell middens throughout Europe. The Romans started cultivating O. edulis in ponds over 2000 years ago and some of their aquaculture techniques are still in use today.

During the late 1700s and the 1800s, native oysters were seen as the “poor man’s” food. Millions were harvested each year to feed the growing urban populations of the Industrial Revolution. The measure then of how rich you were was not how many oysters were in your beef and oyster pie but how much beef.

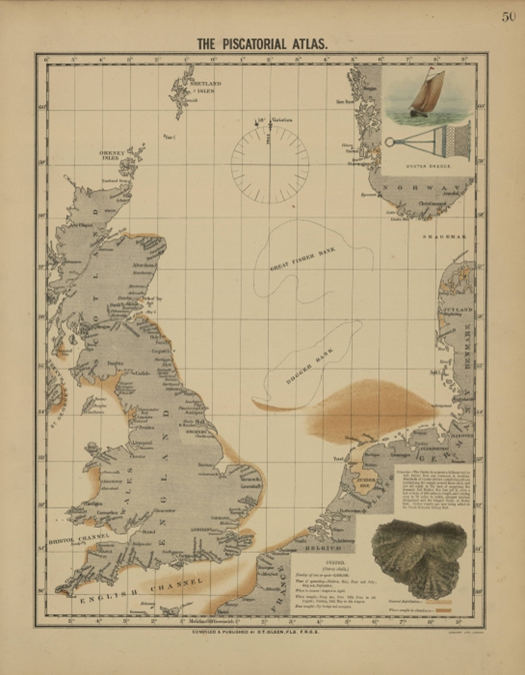

Up until the mid to late 1800s, Scottish waters (Figure 2) supported profitable native oyster fisheries. For example, the oyster “scalps” in the Firth of Forth at that time covered an area larger than the City of Edinburgh. In their heyday, the beds yielded up to 30 million oysters annually (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Hand dredging for native oysters during the 1800s in the Firth of Forth

Continued over-exploitation, including Scottish and foreign fishers removing juveniles to restock other depleted fisheries, pollution and other factors led to declines in stocks and, in some areas, especially on the east coast, the extirpation of the oyster beds. The native oyster’s reproductive strategy means that once population densities fall below a certain level, they are unlikely to be able to breed successfully and recover (Allee effect). Recent surveys have recorded no living oysters in the Firth of Forth.

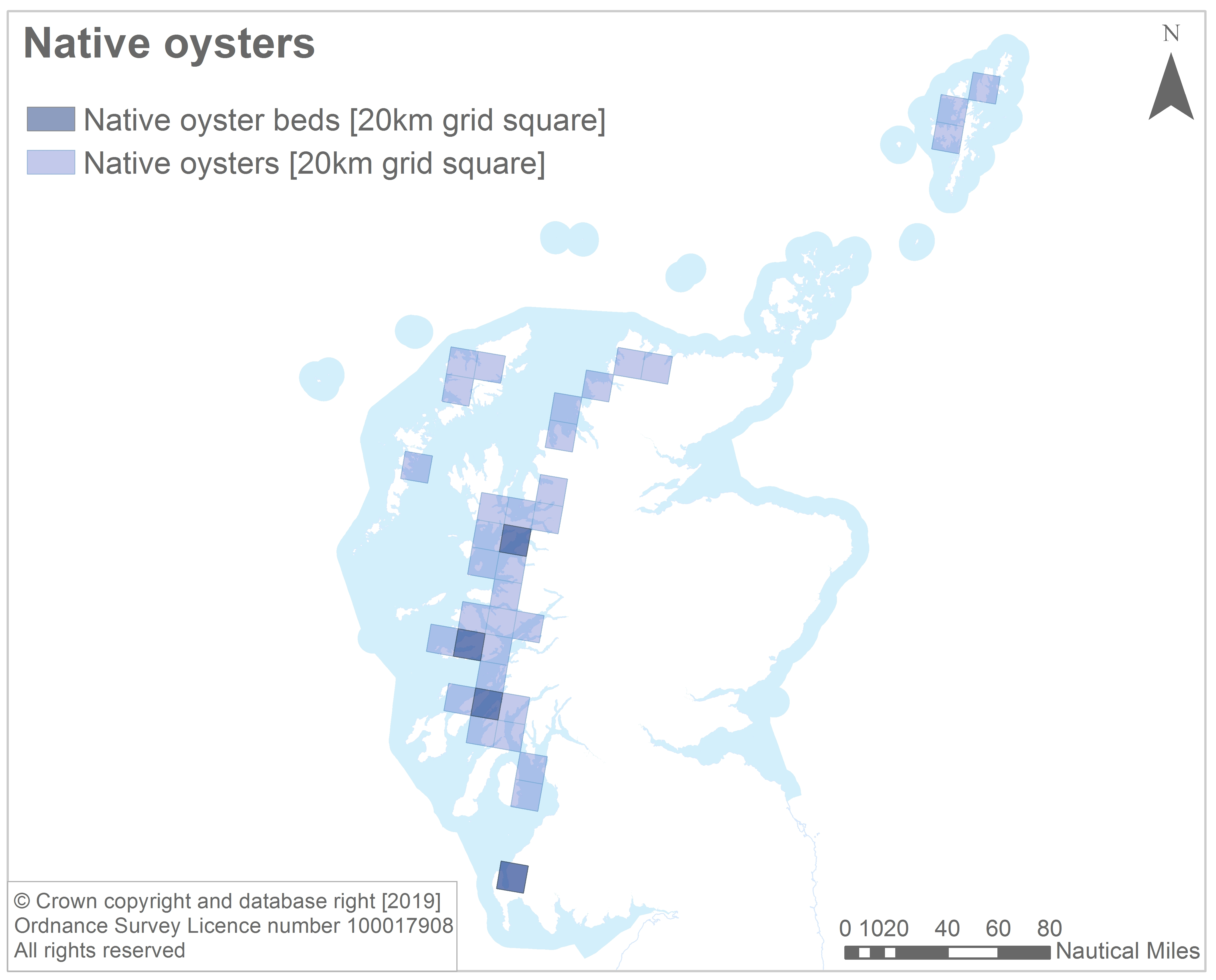

Today, Scotland has scattered remnant populations along the west coast, and around the Western Isles and Shetland (Figure 4). Loch Ryan is now Scotland’s only remaining native oyster fishery, although there is some small scale aquaculture production on the west coast (University Marine Biological Station Millport, 2007; Shelmerdine & Leslie, 2010).

The decline in native oyster populations led the aquaculture industry to experiment with non-native species, with the result that the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea or Magallana gigas) is now widely grown. Today, this accounts for a large proportion of European oyster production (see Aquaculture section) and is the species most likely to be found in the shops. This oyster is cultivated in bags on trestles on the shore and, whilst much stock is bred in hatcheries to be sterile, there is the potential for the species to become established in the wild.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in protecting, regenerating and restoring Ostrea edulis populations in European waters. This has largely been driven by recognition of their ecological importance as part of a healthy marine ecosystem. Oysters act as ecosystem engineers, providing complex habitat for a wide variety of other species (one single oyster shell can host over 100 species of marine flora and fauna). Consequently, oyster beds/ reefs have been likened to a temperate water equivalent of tropical coral reefs in terms of biodiversity (Beck et al., 2011). As with other bivalve molluscs, they feed by filtering organic particles from the water and are understood to improve water quality (Beck et al., 2011). Oysters may also play a role in protecting seagrass beds and coastal features from smothering and erosion (Beck et al., 2011).

The importance of native oysters (Figure 6) as part of the natural heritage and their need for protection is recognised in a number of ways. Under the OSPAR Convention, the native oyster and oyster beds are included in the list of ‘Threatened and/or Declining Species and Habitats’. Accordingly, the native oyster is a Scottish Priority Marine Feature and is included in the Scottish Marine Protected Area network. The Loch Sween Marine Protected Area has the native oyster as one of its protected features.

The main threats to native oysters today are illegal harvesting, invasive non-native species, and disease. The aim for the conservation for Ostrea edulis in Scotland is to protect and enhance the existing populations and to restore the species to its natural range, where appropriate. These are aimed at strengthening native oyster populations and building their resilience to human threats and climate change. In recent years, the Dornoch Environmental Enhancement Project (DEEP) has started a large-scale, long-term project to restore Ostrea edulis to the Dornoch Firth on the east coast.

Other, smaller scale, community led projects have also started working to enhance and restore populations on the west coast. For restoration projects of any size in Scottish waters, NatureScot has an advisory role (to both Government and the projects) to ensure these are carried out responsibly and adhere to, for example, The Scottish Code for Conservation Translocations. In certain cases, NatureScot licensing may also be required. By the next assessment of Scotland’s seas it will be possible to report a wider distribution of native oysters in Scottish waters.

The marine environment is home to a wide variety of invertebrates, many of which have no (e.g.Echinoderms – sea urchins, starfish, etc.) or few representatives in freshwater (e.g. Cnidarians – anemones and corals). A very small percentage of the invertebrate fauna are of commercial value, including Crustacea – e.g. crabs, lobster and Nephrops (aka langoustine or scampi or prawns) and Molluscs – e.g. oysters, scallops and razor fish. The Commercial shellfish assessment covers the three species of greatest economic importance – Nephrops, scallops and brown crabs – which together make up 90% of the total value of Scottish shellfish landings – as well as queen scallops, razor fish, squid, and whelks. The Nephrops assessment is based on annual ICES surveys, for the other species the results are from triennial assessments carried out by Marine Scotland. The Case study: Native oysters highlights the consequences of historical mismanagement and over-exploitation of wild stocks, but also illustrates that with sufficient ambition and resolve there is the potential to reverse such declines.

Links and resources

|

, 2011. Oyster Reefs at Risk and Recommendations for Conservation, Restoration, and Management. BioScience, 61(2), pp.107 - 116. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/61/2/107/242615. |

|

, 2010. Restocking of the native oyster, Ostrea edulis, in Shetland: habitat identification study, Inverness: Scottish Natural Heritage. Available at: https://www.nature.scot/naturescot-commissioned-report-396-restocking-native-oyster-ostrea-edulis-shetland-habitat. |

|

, 2007. Conservation of the native oyster Ostrea edulis in Scotland, Inverness: Scottish Natural Heritage. Available at: https://www.nature.scot/naturescot-commissioned-report-251-conservation-native-oyster-ostrea-edulis-scotland. |