Characteristics of some biogenic habitats (i.e. fragile habitats formed by key animal or algal species that consolidate and/or stand proud of the seabed) lend themselves to charting the effects of a range of anthropogenic activities including towed, bottom-contacting fishing. Abrasion caused by the passage of mobile gears can result in the loss or deterioration of biogenic material that differs markedly from surrounding habitats, with the change in appearance often clearly discernible using a range of widely available survey techniques.

This is one of two case study examples from nearshore waters produced to accompany the Predicted extent of physical disturbance to seafloor assessment which uses fisheries activity data to predict likely levels of disturbance to seabed habitats across Scottish waters. Observed impacts of scallop dredging on flame shell beds in Loch Carron in 2017 are considered separately (see Case study: Protecting the Loch Carron flame shell beds).

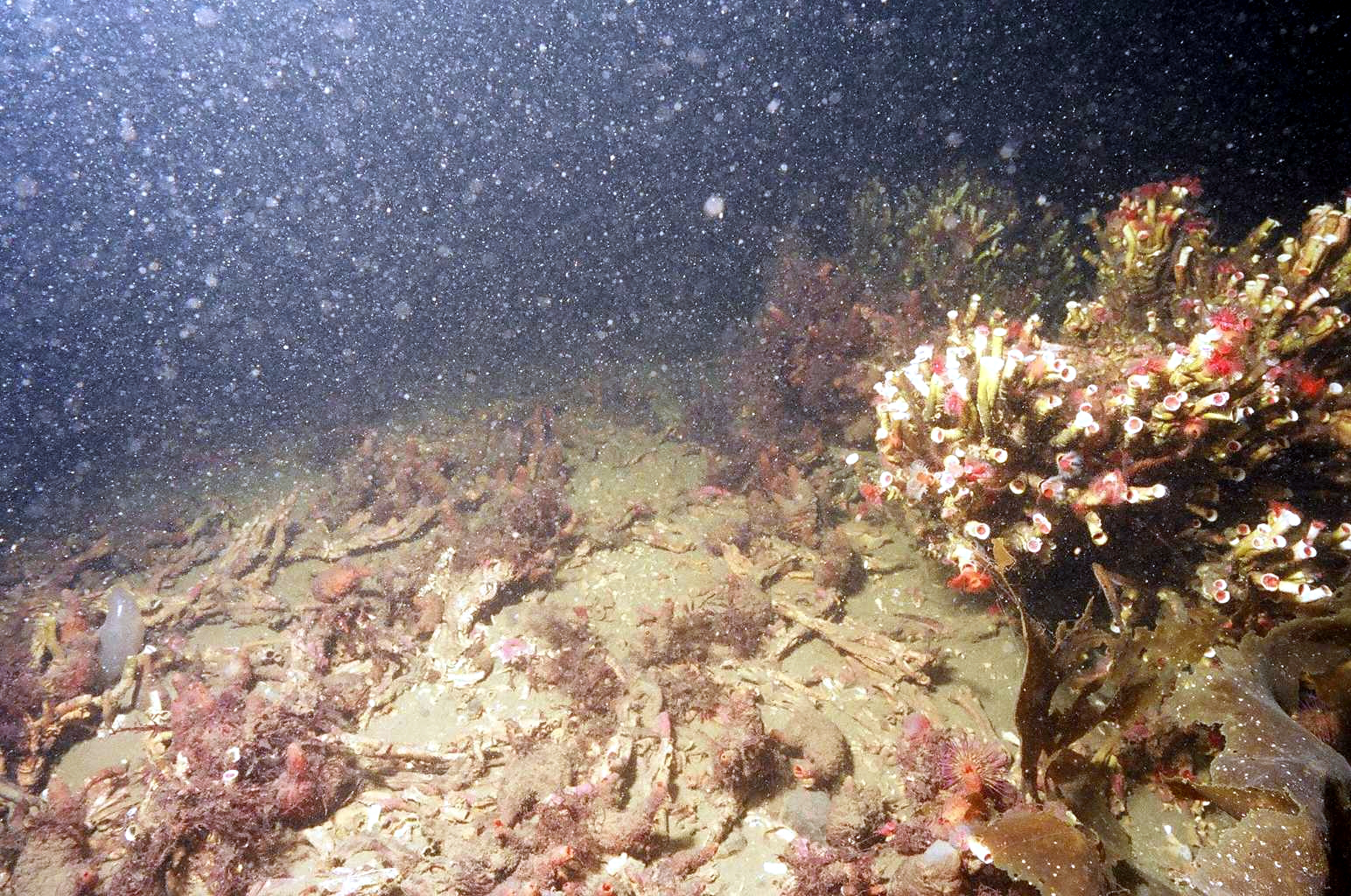

Visual evidence of the impact of demersal fishing, presumably by dredge, was first observed in Loch Creran, a small sea loch on the west coast of Scotland, in 1998 in the form of 3 - 4 m wide tracks passing through an area of dense aggregations of the organ-pipe worm (Serpula vermicularis) (Figure 1). Bushy clumps of worm tubes grow vertically up from the seabed and their complex three dimensional structures provide shelter and habitat for a wide range of other plants and animals. Serpulid aggregations are a Priority Marine Feature in Scottish waters (see Case study: Priority Marine Features). The aggregations are of sufficient size in Loch Creran (up to 75 cm in height and 1-2 m in diameter) to be recognised as biogenic reefs, a protected feature of a Special Area of Conservation in this location. The reefs in Loch Creran represent the best example and the largest known extent of this habitat in the world. Smaller aggregations are currently only known from two other Scottish sea lochs (Loch Teacuis and Loch Ailort), three locations in Ireland and two in Italy (Sanfilippo et al., 2012; SNH, 2018).

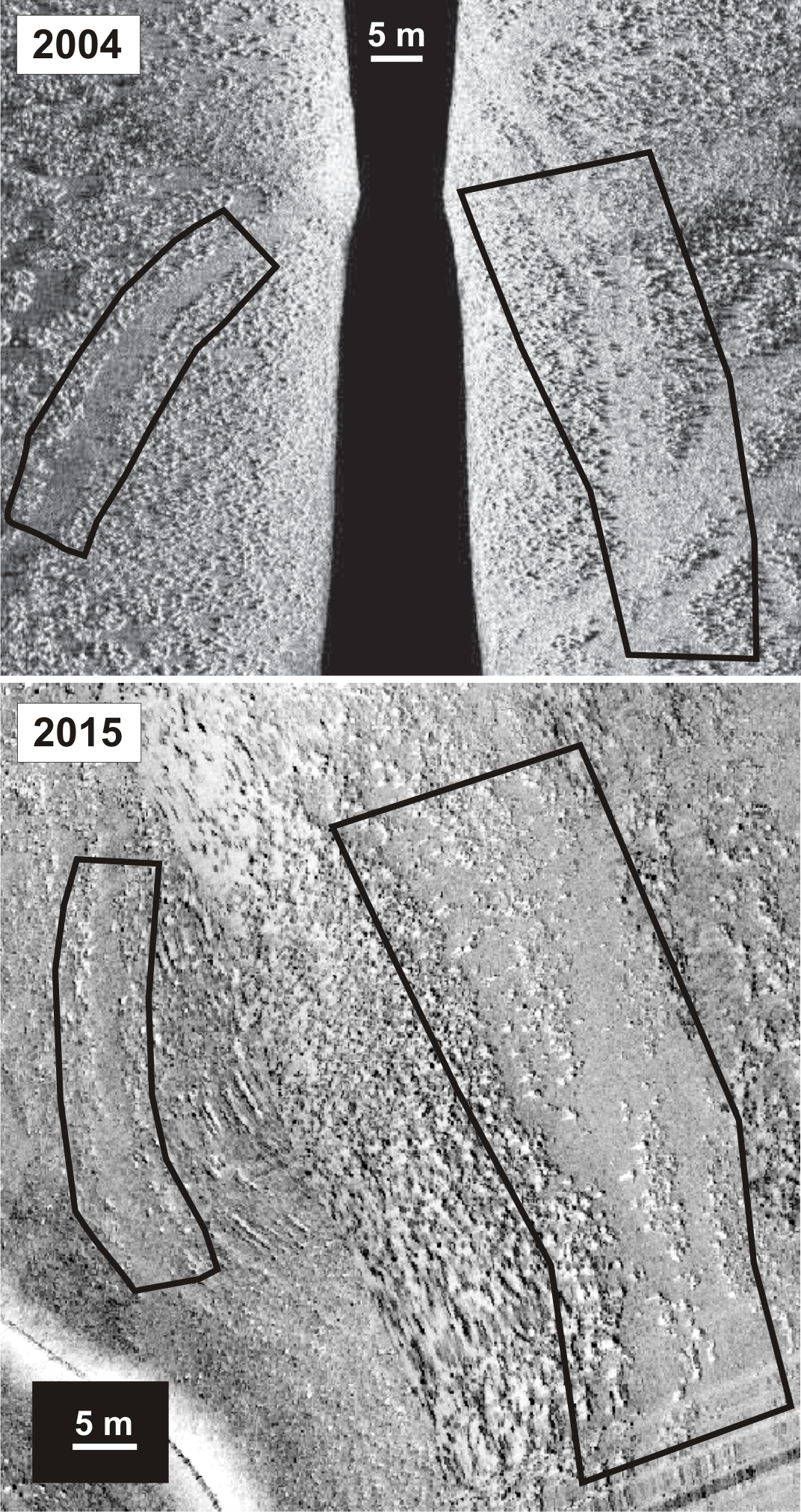

A 2005 Scottish Natural Heritage survey estimated that around 11% of the habitat in one of the principal reef areas of the loch had been damaged by this activity (Moore et al., 2006). Recent monitoring work has revealed little recovery of the habitat after 17 years (Moore et al., 2019) with the original tracks still clearly discernible on the most recent sidescan sonar imagery (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sidescan imagery from surveys in 2004 and 2015 showing persistence of demersal fishing tracks through serpulid reef habitat in the same location in Loch Creran, Argyll. Similar regions of track delimited by black polygons. Upper image (2004) © St. Andrews University and Heriot-Watt University; lower image (2015) GeoSurv Ltd © NatureScot.

Loch Creran was proposed as a protected area in 2001 and formally designated in 2005. Fisheries management measures prohibiting scallop dredging from the loch were implemented in 2007 (SSI 2007/185) and subsequently revised in 2016 (Marine Scotland, 2016 / SSI 2015/435).

This case study illustrates that recovery in some seabed habitats can take a very long time and may not be possible if supporting habitats are modified by the activity e.g. through the removal of stones and other hard settlement substrates used by the serpulid worms on the muddy loch sediments or due to other changes in the loch system e.g. an increase in predators such as urchins and starfish.

The implementation of fisheries management measures and appropriate assessment of other licensed activities will continue to help to mitigate against future anthropogenic declines in seabed habitats within the Loch Creran protected area. This is particularly important because recent studies (Moore et al., 2020) concluded that reef fragmentation is now widespread, estimating that ~20% of all serpulid habitat in the loch has been lost since 2005. The authors postulate that the broader degradation observed may be natural and form part of a longer-term cycle. Ongoing monitoring will be required to determine whether serpulid aggregations are ever able to re-establish along the formerly fished tracks during future recovery phases.

Conservation of serpulid aggregations needs to be informed by a better understanding of the factors influencing reef development and the condition or process of deterioration with age. The potential to enhance recovery and give nature a helping hand in Loch Creran is the subject of ongoing research by Heriot-Watt University (see Case study: Biogenic habitat enhancement). A localised restoration programme in an area where the reefs have effectively become extinct could clarify the potential for such an approach should natural recovery not occur and might also serve as an experimental and supply site for essential future studies into the population dynamics of Serpula vermicularis in the loch (Moore et al., 2020).

Scotland has an extensive and varied coastline comprising approximately 50% rocky and 50% sedimentary intertidal habitat. Large stretches of the Mainland west coast and Northern Isles are predominantly rocky whereas on the west coast of the Outer Hebrides and the Mainland east coast it is much more patchy with rocky shores and cliffs interspersed by large stretches of sandy and muddy coastline. Intertidal habitats are affected by numerous physical variables including wave exposure, salinity, temperature and tides which dictate what animals and plants are found on specific shores. The subtidal communities are strongly affected by factors such as the availability of light, wave action, tidal stream strength and salinity. Rocky shallow continental shelf habitats are typically dominated by seaweeds and in deeper areas below the photic zone (about 50 m) communities comprise exclusively animals. Shallow subtidal sediments in places support habitats such as seagrass beds and maerl, a red seaweed with a hard chalky skeleton that forms small twig-like nodules which accumulate to form loosely interlocking beds, creating the ideal habitat for a diverse community of organisms. Typically sedimentary habitats are dominated by a range of burrowing animal species.

The Biogenic habitats assessment catalogues the loss in extent of six biogenic habitats (all Priority Marine Features): blue mussel, horse mussel, flame shell, maerl, seagrass beds, and serpulid aggregations. The Predicted extent of physical disturbance to seafloor assessment uses the degree of exposure to demersal fishing activity as a proxy for habitat condition. The Intertidal seagrass assessment is a first attempt to understand the ecological health of Scottish intertidal seagrass and is restricted to six sites.

The Case study: Biogenic habitat enhancement highlights the efforts now being made to enhance the status of some biogenic habitats through activities aimed at aiding their recovery and restoration. In other cases, where damage to Priority Marine Features has occurred, positive action is taken as demonstrated in the Case study: Protecting the Loch Carron flame shell beds where emergency measures were put in place to prevent further damage and subsequently a Marine protected Area was designated. The fact the prevention is better than cure is illustrated by the Case study: Persistent damage to the Loch Creran serpulid reefs where damage that was first observed in 1998 still shows little evidence of recovery. The value of long-term monitoring of specific sites is illustrated by the Case study: Intertidal rock which highlights how looking at changes at a community scale helps separate natural variations on species abundances from longer term community trends. The growing awareness of natural capital and ecosystem services provided by the marine environment is illustrated by the three case studies Case study: Blue carbon in Scottish maerl beds; Case study: Blue carbon in Scottish marine sedimentary environments; Case study: Blue carbon: the contribution from seaweed detritus which highlight the importance of marine habitats in climate change mitigation through the capture and storage of blue carbon, and the need for the protection of such habitats from various anthropogenic activities. Despite a long history of intertidal and subtidal survey work there remains significant gaps in knowledge. The Case study: Seabed habitats in territorial waters - the evolving knowledge-base charts the ongoing surveys that have been undertaken by government agencies and citizen science initiatives to further expand and improve the knowledge base.

The seas around Scotland are home to a wide variety of animals and plants and are of international importance as a stronghold for many species. Whilst the protection of the wider environment through the management of various activities is essential, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) have an equally important role to play in the protection and conservation of key habitats and species. There are now 230 MPAs covering 37% of Scotland’s marine environment (at December 2020, it was 22% in 2018 at the end of the assessment period) comprising MPAs for nature conservation (Nature Conservation MPAs; Special Areas of Conservation (SACs); Special Protection Areas (SPAs); Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs); and Ramsar sites), MPAs for other purposes (Demonstration and Research MPAs; and Historic MPAs), and Other Area-based Measures. Work continues to implement all the necessary management measures and the on-going monitoring necessary to determine the effectiveness of the protection afforded by the MPAs. The Case study: Protecting the Loch Carron flame shell beds documents the emergency measures put in place to prevent further damage after scallop dredgers destroyed part of the bed. In other cases, it is apparent that prevention is better than cure – the Case study: Persistent damage to the Loch Creran serpulid reefs where damage first recorded in 1998 still shows little evidence of recovery. The Case study: Flapper skate – Loch Sunart to the Sound of Jura MPA describes how the on-going monitoring involving recreational anglers has not only improved our understanding of the ecology but also the information necessary for determining the management measures needed to ensure their protection.

Perhaps one of the greatest challenges is balancing the need for protection and therefore control of certain activities with the resulting possible socio-economic impacts. The Case study: Socio-economic impacts of marine protected areas describes the outcomes of an initial assessment of the evidence and views of the impact of MPA designation. These are some initial findings from only 2-3 years after designation and whilst there is evidence in some areas that fishing has been made more challenging there are also early signs of positive environmental and community impacts. The lessons from other parts of the world is that to get a full and balanced picture of the effects of MPA designation takes time.