Clean and safe seas

Headline facts

59% of shellfish-growing waters had the highest possible microbiological standards of water quality (Class A) in the 2019/20 classification. This was an improvement from the 40% reported in 2011.

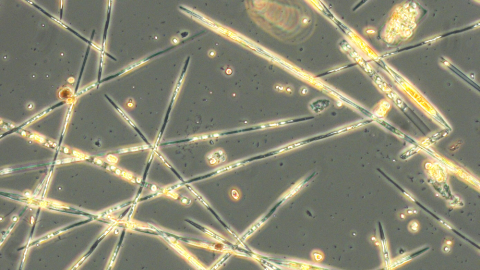

Shellfish toxins continue to cause issues in Scotland leading to closure of shellfish harvesting sites lasting, in some cases, for up to six months.

Bathing waters with an excellent classification have increased from 16 (2015) to 28 (2018), which is good for tourism.

Marine litter on beaches continues to be a problem in many areas, with the amount of litter being highest in Firth of Forth harbours and lowest in Orkney.

Sea-floor litter, mainly plastics, was observed in 44% of trawls with the highest densities occurring in the North Sea.

Impulsive noise in the frequency range 10 Hz – 10 kHz, which can affect marine organisms from fish to marine mammals, was highly variable both in location and between years (2015 – 2017), the variation depending largely on the industrial developments and surveys taking place each year.

For all Scottish Marine Regions (SMRs), winter nutrient concentrations are at levels that cause no concern.

Dissolved oxygen concentrations are above levels required to maintain healthy marine ecosystems in all SMRs except the inner Clyde where there are localised low dissolved oxygen issues.

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are unlikely to cause adverse effects in fish and shellfish.

Contamination by synthetic organic chemicals, heavy metals, natural toxins, plastics, bacteria and viruses, nutrient imbalance, or anthropogenic sources of noise and vibration, can affect the physical health, behaviour and functioning of marine species and habitats. However, many of Scotland’s marine species, habitats and physical processes have important roles in processing, detoxifying and protecting the wider ecosystem. For example, seagrass beds in the Dornoch Firth act as shelter, nurseries, spawning and feeding areas. Biogenic reefs, such as those created by the horse mussel (Modiolus modiolus) can be important with respect to the enhancement of biogeochemical cycling and the sequestration of nutrients. In addition, a build-up of Modiolus modiolus shell material is thought to make an important contribution to carbon sequestration. This is exemplified by the horse mussel bed off Noss Head, Caithness (Figure 1), which is the largest known in Scotland at approximately 3.85 km2 and is estimated to contain a minimum of 15,377 tonnes stored carbon (Burrows, 2014). The potential to improve water quality is a key ecosystem service provided by Modiolus modiolus reefs. However, this may be at risk as a result of the warming of the waters around Scotland arising from climate change which may limit the ability of the horse mussel to form the necessary clumps.

The natural processes exhibited by species and habitats in the seas around Scotland with respect to the breakdown and detoxification of anthropogenic sources of contaminants, pollutants or excess nutrients are limited either by the extent of these species and habitats or when thresholds for natural regulation are exceeded. Ultimately, the health of marine species can be compromised. Scotland is taking measures to ensure that the concentrations of contaminants and nutrients are below those which will cause unintended or unacceptable biological effects. This has resulted in eutrophication not being a problem in the waters around Scotland. In addition, the concentration of individual contaminants rarely exceed assessment criteria which means that it is unlikely that adverse effects will be observed. However, this relates to the species in which the contaminants have been assessed. Biomagnification (chemical concentrations in plants or animals increase from transfer through the food web meaning that predators accumulate greater concentrations of a particular chemical than their prey) can result in top marine predators, such as whales and dolphins, containing very high concentrations of contaminants raising the possibility of biological effects and consequences for biodiversity. As highlighted in the Case Study on PCBs in grey seals from the Isle of May, Firth of Forth, PCBs continue to exert biological effects on grey seals at concentrations experienced in the wild, even though they are 7 - 113 times below what are normally considered to be marine mammal toxicity thresholds’. Another issue which needs to be investigated is the effects of exposure to multiple contaminants, as marine biota are not exposed to individual compounds. In addition, the range of contaminants present in the seas around Scotland reflects the discharges, emissions and losses from land sources with pharmaceuticals such as venlafaxine and desmethylvenlafxine detected in the Clyde and Forth Estuaries while amphetamine and propranolol were detected in the Clyde Estuary (McKenzie et al., 2020). The implications of this for the ecosystem services has yet to be fully understood.

Scotland has in place processes to ensure that the level of Escherichia coli is within safe limits and, together with an effective biotoxin monitoring programme, these processes ensure that shellfish can continue to be exploited with nutritional and economic benefits for people.

Contaminants can compromise the health and aesthetic qualities of the marine and coastal environment, with negative consequences for recreation, tourism and quality of life. Efforts to stem the flow of plastics and other litter into the marine environment, and to clean up where it has already accumulated, should have lasting economic and societal benefits. Scotland, as a nation of the UK, continues to reduce emissions, discharges and losses of hazardous substances and nutrients in line with the requirements of the OSPAR Commission resulting in the concentrations of contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) generally being below the OSPAR threshold at which adverse effects occur in the species analysed (fish and shellfish). Marine litter continues to be an issue (Figure 2), especially plastic, with the associated concerns in respect of the impact on recreation, tourism and quality of life.

All outfalls, wastewater treatment and industrial effluent in Scotland, are subject to strict environmental controls. Significant improvements have been made which have resulted, for example, in increased water quality in Scotland’s estuaries. The ability of the marine ecosystem to disperse and assimilate waste is an ecosystem service from which individuals and organisations, including businesses, gain significant benefit not only in terms of the disposal of waste but also cost savings compared to alternative means.

The implications of underwater noise, be it continuous or impulsive and vibration, are not as well understood as those associated with many contaminants/pollutants but range from relatively rare occurrences of death and physical injury to either more widespread or temporary changes to animal behaviour and distribution. Direct impacts on cetaceans and seals are of primary concern, potentially influencing tourism and recreation opportunities. There may be consequences for the distribution and spawning success of some fish and shellfish species; a better understanding of species sensitivity to noise would help inform the measures necessary to prevent the unintended consequences to these natural resources and related functions. SMA2020 contains assessments of both impulsive and continuous noise. These provide some data, but linking cause and effect will be more difficult.

Overall, clean seas ensure the delivery of a range of ecosystem services and Scotland benefits from seas that are often at the lower end of contaminant scales. However, unless there is improved understanding of the cumulative effects that take account of the impacts of the wide range of contaminants in the sea, exposure to anthropogenic noise, the presence of micro- and nano-particles, and the additional bacteria and viruses that are in the sea due to anthropogenic activities, there is a risk that some of the ecosystem services will be compromised.

Literature

|

, 2020. Multi-residue enantioselective determination of emerging drug contaminants in seawater by solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical Methods, 12(22), pp.2881 - 2892. |